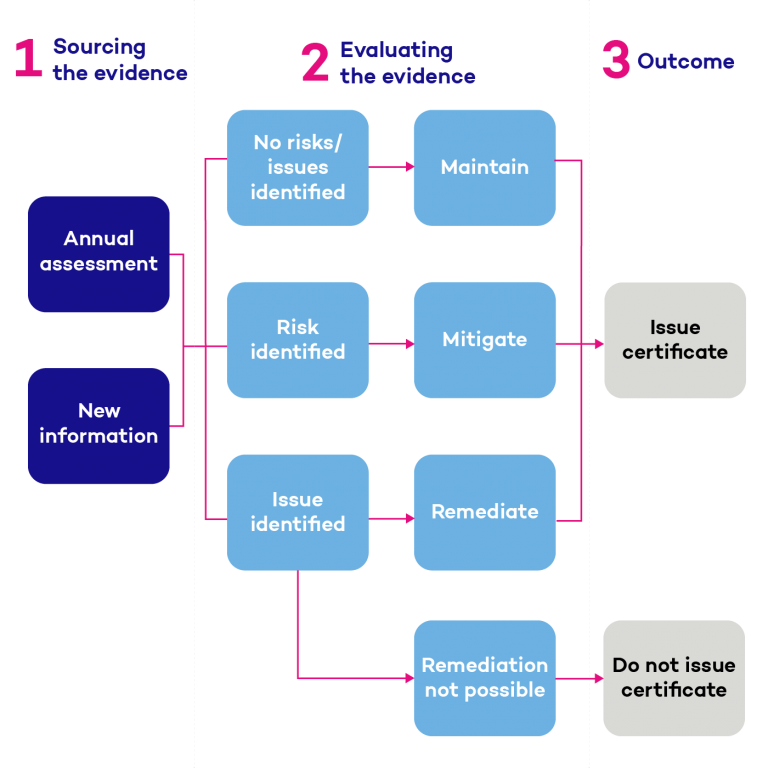

Having looked at the types of fit and proper assessment that firms might be required to perform, let’s look at the form a typical fit and proper assessment may take.

Fit and proper assessments can be broken down into four distinct stages:

- First, “sourcing the evidence” needed to perform the fit and proper assessment,

- Second, “evaluating the evidence” that has been gathered,

- Third, “determining an outcome” – in other words, deciding whether or not to issue the ‘fit and proper’ certificate, and taking action to mitigate risks or remediate an issue where necessary; and

- Finally, recording the outcome.

We’ll look at each of these in more detail.

Sourcing the evidence

Before commencing fit and proper testing, firms should develop a standardised approach to the different types of evidence that are required in each possible fit and proper assessment scenario.

In reality, much of the evidence that feeds into a fit and proper assessment will have been gathered as part of a firm’s other processes (for example, appraisals, disciplinary procedures, routine screening etc). In addition, staff members should be aware of what is required of them – in terms of the type of evidence they must produce and the frequency with which it must produced.

As such, sourcing the evidence required in order to enable a fit and proper assessment to be conducted should, in most cases, be relatively straightforward.

Nonetheless, the collaborative nature of fit and proper evidence gathering needs to be recognised. As the Banking Standards Board makes clear in its guidance on fit and proper testing, ‘demonstrating fitness and propriety is not a ‘one-off’ annual event at the point of assessment, but is rather an ongoing commitment by both the individual and their employer’. It therefore follows that both the firm and the individual being assessed are responsible for ensuring that fit and proper evidence is maintained and up-to-date. In some circumstances, the individual will be primarily responsible for sourcing evidence. An example would include documentation evidencing personal development. Obviously, it may often be the case that an employer will have to support an individual in meeting this responsibility. In other circumstances, the employer will be primarily responsible for sourcing the evidence needed to conduct a fit and proper assessment. An example here might include performance assessments or screening checks.

There are no hard-and-fast rules as to the type of evidence that should be used (or not used) with respect to different types of fit and proper assessment. However, hopefully this table provides useful guidance as to the evidence you may consider using in each circumstance.

| Evidence Source | New Role Assessment | Annual Assessment | Triggered Assessment | In-Year Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job description | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Application form | Yes | |||

| C.V. | Yes | |||

| Interview notes | Yes | |||

| Character/professional references | Yes | |||

| Assessment centre results | Yes | |||

| Rationale for hiring | Yes | |||

| Criminal records checks | Yes | Yes | Depends on circumstances | Depends on circumstances |

| Credit reference agency checks | Yes | Yes | Depends on circumstances | Depends on circumstances |

| Qualifications | Yes | |||

| Verification of qualifications | Yes | |||

| Regulatory references | Yes | |||

| Updated regulatory references | Yes | |||

| Training and induction programmes | Yes | |||

| Continuing Professional Development (CPD) records | Yes | Yes | ||

| Individual portfolio of achievement | Yes | Yes | ||

| Behaviour performance ratings (e.g. customer outcomes or balanced scorecard) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| 360 degree feedback | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Annual appraisal | Yes | |||

| Disciplinary proceedings | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Financial soundness questionnaire | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Retrospective self-declarations* | Yes | Yes | Depends on circumstances | Depends on circumstances |

| Prospective self-declarations** | Yes | Yes | Depends on circumstances | Depends on circumstances |

* for example, as to whether or not the individual has a criminal record

** for example, a commitment to uphold high standards of behaviour

In many ways, the first and most obvious piece of evidence for firms to gather is the individual’s up-to-date job description. After all, the assessment must be performed in relation to the role that the individual is actually performing at the time the assessment is performed.

Obviously, consideration also needs to be given to HOW OFTEN information from each source should be gathered.

Let’s look at some specific evidence sources in a little bit more detail.

Onboarding information

Generally, the information gathered when an individual joins a firm (an application form, a CV, interview notes, assessment centre results etc.) remains fairly static. As such, it can usually be relied on in subsequent fit and proper assessments. There is one obvious exception to this – being a regulatory reference which is subsequently updated by a previous employer.

Screening checks

When we talk about screening checks (sometimes referred to as ‘vetting’) we are talking about things like credit reference check or a Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) checks (in other words, criminal records checks). Firms will need to determine at what points screening checks should be performed (for example on taking up a new role) and with what frequency they need to be refreshed.

The Banking Standards Board provides a table which provides a non-exhaustive list of the types of screening check which a firm may consider in determining fitness and propriety under each separate ‘pillar’. That table is summarised here.

| Evidence | Honesty, Integrity and Reputation | Competence and Capability | Financial Soundness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disclosure and barring services check (criminal records check) | Yes | ||

| Clearing house check (e.g. LCH) | Yes | ||

| Staff fraud checks | Yes | ||

| Company searches | Yes | ||

| Sanctions checks | Yes | ||

| Professional body registers | Yes | Yes | |

| Credit reference agency checks | Yes | ||

| County court judgments | Yes | ||

| Bankruptcy orders | Yes |

Where a candidate has spent a considerable time working or living outside of the UK, firms should consider undertaking an equivalent check with the appropriate foreign regulatory body, where available.

As an aside, firms may – if they wish to do so – choose to employ criminal record checks for some employees who are not applying for positions under the SM&CR. Of course, the member of staff will have to consent to this.

Self-declarations

Self-declarations can be both retrospective (“I confirm that I have not been made bankrupt in the last 12 months”) as well as prospective (“I confirm that I will uphold the highest standards for the business.”). They play an important part in confirming fitness and propriety and flushing out potential Certification Risks and Certification Issues.

Firms should determine:

- what type of self-declaration is required,

- when it is required, and

- at what period it needs to be refreshed.

Self-declarations are likely to play an important part of any new role assessment as well as annual assessment. They may also be relevant with respect to an in-year assessment or a triggered assessment – but this will largely depend on the circumstances which gave rise to the in-year or triggered assessment itself.

Self-declarations can relate to such matters as:

- Management of conflicts of interest,

- Acting in conformity with the Conduct Rules,

- Notification regarding criminal convictions or cautions,

- Notification regarding bankruptcies,

- Notification regarding court judgements,

- Notifications regarding decisions of regulators or professional bodies, or

- Disclosure of information pertaining to fitness and propriety generally.

Care should be taken to ensure that any ostensibly adverse response to a self-declaration should NOT, simply of itself, be taken as meaning that the individual is no longer fit and proper to perform his or her role. Rather, the surrounding circumstances should be fully investigated and an element of judgement applied. For example, an acknowledgment by an individual that he or she is facing financial difficulties does not, of itself, mean that the individual is not financially sound. It may well be that the individual has already formulated and is in the process of implementing a plan to remedy the situation.

The Banking Standards Board has provided a non-exhaustive list of the types of self-declaration that firms could seek from staff as well as the ‘pillar’ of fitness and propriety to which each self-declaration relates.

| Self-declaration | General | Honesty, Integrity and Reputation | Competence and Capability | Financial Soundness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The individual understands how the Conduct Rules apply to their specific job roles and commits to discharge their responsibilities professionally | Yes | |||

| Based on their self-assessment, the individual discloses anything they feel is relevant to their fitness and propriety | Yes | |||

| The individual is not subject to a criminal investigation/proceedings/caution/conviction which raises a concern about their fitness and propriety | Yes | |||

| The individual is not involved/has not been involved in a civil dispute which raises a concern about their fitness and propriety | Yes | |||

| The individual is not engaged in an internal relationship which could give rise to a real or perceived conflict of interest (in line with firm policy) | Yes | |||

| The individual is not subject to disciplinary proceedings by a professional membership body (where relevant) | Yes | |||

| The individual has not been responsible for/involved in anything that has or could bring the individual/firm/industry into disrepute | Yes | |||

| The individual is competent and capable to undertake the role as specified in his/her job description | Yes | |||

| The individual is not subject to any arrangements/judgments that could call into question their financial soundness (e.g. County Court Judgement or bankruptcy) | Yes | |||

| The individual is not aware of any financial commitments which may call into question their financial soundness (e.g. inability to meet loans due) | Yes | |||

| The individual is behaving in a financially responsible way | Yes |

Regulatory references

SYSC 22 is the chapter of the FCA Handbook which deals with the requirement to obtain regulatory references from a previous employer when a firm is planning to appoint someone to perform a Certification Function as part of its assessment of whether that person is fit and proper.[1]

Firms which are subject to the SM&CR must take reasonable steps to obtain appropriate references from a candidate’s previous employers before appointing a:

- Senior Manager,

- Certification Employee, or

- NED whose appointment is not pre-approved by a regulator but who appointment is notified to the regulator afterwards (a “Notified NED”).

The regulatory references should cover the individual’s employment for the previous six years. This requirement applies regardless of whether or not the previous employer was an authorised firm.

Regulatory references for Senior Manager appointments (in other words, those that require FCA approval) should, ideally, be obtained BEFORE the application for approval is made to the FCA. With respect to Certification Employees, regulatory references should be obtained BEFORE a fit and proper certificate is issued to the individual. Nonetheless, the FCA does recognise that this might not always be possible (for example, where a need arises to fill an unforeseen Senior Manager vacancy). In these circumstances, the firm must obtain regulatory references no later than one month BEFORE the end of the FCA application process. However, there is one exemption to this rule. If the firm requesting the regulatory reference or the firm providing the regulatory reference would be required to make a public announcement, a regulatory reference can be obtained AT ANY TIME before the end of the application process. It goes without saying that if a regulatory reference which is obtained later than would normally be the case raises concerns about the fitness and propriety of the individual who is the subject of the reference, then the firm should revisit the individual’s suitability for the role.

Regulatory references form a key plank of fit and proper assessments. A properly constructed regulatory reference should disclose whether, at any point in the previous six years, the individual to whom the regulatory reference relates:

- has breached the Conduct Rules,

- has been deemed not fit and proper to perform his or her role (and why), or

- has been subject to disciplinary proceedings (explaining why and detailing the sanction).

However, firms need to be wary of becoming over-reliant on the contents of regulatory references for the simple reason that they may not contain all of the information that is relevant to an individual’s fitness and propriety.

More specifically, when considering the information they intend to disclose in any reference, firms are expected to exercise judgement – balancing the need to be transparent (in order to address the “rolling bad apple” phenomenon) against the need to be fair to former employees and to comply with any other relevant legal obligations (for example, GDPR). As part of this balancing act, it is important to bear in mind that firms which respond to regulatory references are NOT required to disclose information that has not been properly verified. For example, a firm is not required to include the fact that an ex-employee left while disciplinary proceedings were pending or had started. Why is this? Well, it is thought that the inclusion of this kind of information would tend to imply that there is cause for concern about the ex-employee. However, there may be no proof or evidence that this was actually the case.

As such, regulatory references are best considered as another input into the overall determination as to whether an individual is fit and proper to perform his or her role.

Regulatory references are particularly relevant with respect to new role fitness and propriety assessments. Essentially, the assessor is looking for two things:

- Firstly, whether the regulatory reference provides any kind of evidence that, in a previous role, the individual has done anything to suggest that he or she was not fit and proper for their new role (for example, being dishonest or bringing the firm into disrepute); and

- Secondly, whether there is evidence to positively demonstrate fit and propriety (in practice, a regulatory reference is less likely to address this second point).

[1] SYSC 27.2.7G

Individual portfolio of achievement

An individual portfolio of achievement might not be the first thing that may firms consider when assessing an individual’s fitness and propriety. However, it can be a useful source of information. It can include such things as:

- professional connection websites,

- media profile (if any),

- external publications,

- external training attended,

- qualifications obtained.

In particular, media profiles and publications can provide a useful indication of whether an individual has the “competence and capability” required for a particular position.

Evaluating the evidence

Once the evidence relevant to an individual’s fitness and propriety has been gathered, this information will need to be assessed to determine whether a fit and proper certificate should be issued.

At a high level, under sections 60A and 63F of The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, in assessing whether a person is a fit and proper to perform a Senior Management Function or a Certification Function, a firm must have particular regard to whether that person:

- has obtained a qualification; or

- has undergone, or is undergoing, training; or

- possesses a level of competence; or

- has the personal characteristics[1]

required by rules made by the relevant regulator. Those rules are:

- in the case of very senior employees – SYSC 4.2 and SYSC 4.3A.3R (being the requirement that firm ensures that the management body, as a collective, possesses adequate knowledge, skills and experience to understand the firm’s activities),

- The “competent employees rule”

- This is the rule found in SYSC 5.1.1R which states that firms must employ personnel with the skills, knowledge and expertise necessary for the discharge of the responsibilities allocated to them[2],

- In the case of firms conducting retail activities – the rules specified in TC 2.1.1R, TC 2.1.5BR and TC 2.1.12R, and

- With respect to employees of insurance firms – the rules specified in SYSC 3.1.6R.[3]

Of more practical help on a day-to-day basis are the ‘fit and proper’ requirements of the FCA. These are specified within “FIT” – a chapter of the FCA Handbook. The main criteria to be taken into account when performing fit and proper assessments is specified in FIT 2.[4] Although it is a non-exhaustive list[5] – as we have already seen – the FCA considers that most important[6] criteria are a person’s:

Moreover, the FCA expressly states that it expects firms to adopt “substantially” the same criteria when performing their own fit and proper assessments.[10]

We have already looked at what these concepts mean. In essence, this is what makes fit and proper assessments distinct from, say, a disciplinary process – disciplinary processes do not have such a specific foundation in legislation.

It is also be helpful to consider the factors which the FCA states it takes into consideration when determining the fitness and propriety of an individual applying for authorisation.[11] These include:

- whether the individual has been open with the FCA and disclosed all relevant matters,

- the seriousness of any issue and its relevance to the specific role applied for,

- the time that has passed since any issue occurred, and

- whether the issue relates to an isolated incident or a pattern of adverse behaviour is discernible.

In determining whether an individual is fit and proper to perform his or her role, firms should also consider:

- the activities of the firm for which a function is, or is to be, performed;

- the permission held by the firm;

- the markets within which the firm operates;

- the nature, scale and complexity of the firm’s business; and

- whether the candidate or person has the knowledge, skills and experience to perform the specific role that the candidate or person is intended to perform.[12]

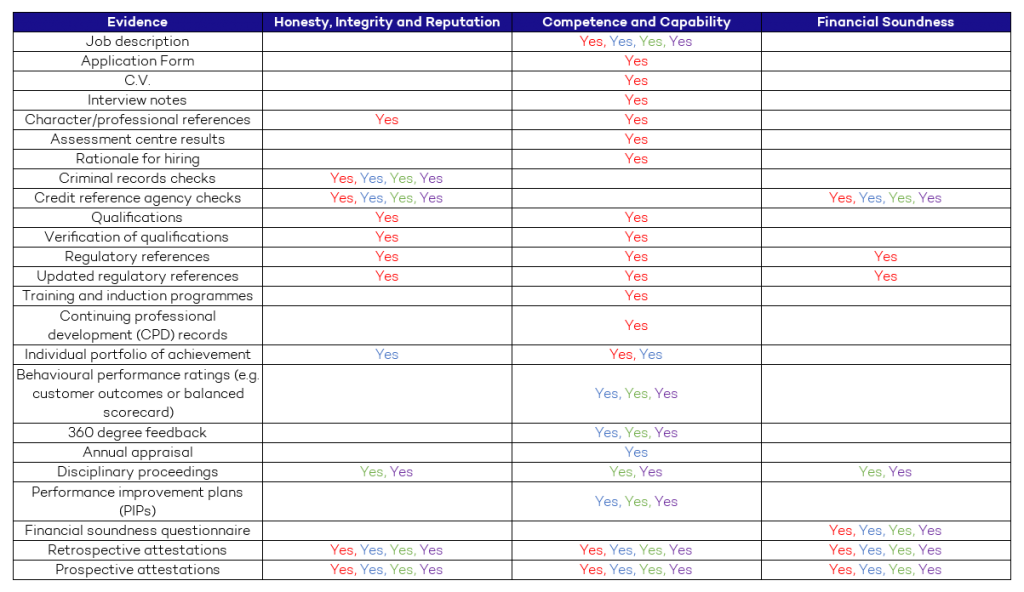

This table summarises the types of information that firms could use to assess fitness and propriety by reference to each ‘pillar’:

[1] FIT 1.2.1BG and SYSC 27.2.5G

[2] FIT 1.1.1G

[3] FIT 1.2.1CG

[4] FIT 1.3.1

[5] FIT 1.3.3G

[6] FIT 1.3.1BG

[7] FIT 2.1

[8] FIT 2.2

[9] FIT 2.3

[10] FIT 1.3.1AG

[11] https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/approved-persons/disclosing-criminal-convictions

[12] FIT 1.3.2G and FIT 1.3.2AG

Red = New role assessment

Blue = Annual assessment

Green = Triggered assessment

Purple = In-year assessment

Some types of evidence are highly relevant to the question of fitness and propriety. For example, a credit reference check is clearly relevant to the question of financial soundness, and a qualification (or lack thereof) is clearly relevant to the question of competence and capability. However, not all evidence gathered as part of a fit and proper assessment is so obviously relevant. Despite a firm’s best endeavours to create a standardised approach to the treatment of fit and proper evidence, there will inevitably come a point when those conducting fit and proper assessments will need to subjectively evaluate the relevance and significance of any piece of evidence within its proper context.

Firms should also consider whether broader organisational factors have played a part in a finding that an individual is not fit and proper to perform his/her role. An example would be the firm’s culture and the way in which it might encourage behaviour that may be inconsistent with the requirement to be ‘fit and proper’. Of course, this does not mean that individuals should be made responsible for a firm’s failings. Equally, however, it should not mean that the concept of personal responsibility is done away with. It means only that this factor should be considered (even if it is concluded that it is irrelevant).

Positive, neutral and negative evidence

When evaluating fit and proper evidence, it can be useful to categorise each piece of evidence as being either positive, neutral or negative with respect to one of the three ‘pillars’ (honesty, integrity and reputation, competence and capability, and financial soundness).

Positive evidence actively demonstrates the individual’s fitness and propriety. An example would be possession of a relevant professional qualification or CPD record.

In contrast, negative evidence actively demonstrates a LACK of fitness and propriety. An example would be a screening check which highlights an issue that had not previously been disclosed by the person being assessed.

Neutral evidence is, as the name suggests, neutral. There is no positive evidence affirming fitness and propriety. However, at the same time, there is no evidence suggesting that an individual MAY NOT be fit and proper.

Mitigating and aggravating factors

When assessing evidence for the purposes of fit and proper testing, it can also be useful to identify the specific factors that would tend to mitigate, or aggravate, the severity of an issue under consideration. This is an important factor in developing a standardised approach to fit and proper testing more generally.

The Banking Standards Board has produced another helpful table in this regard. It contains a non-exhaustive list of factors to consider when evaluating the significance of evidence that might call into question an individual’s fitness and propriety. Some factors act as mitigants whereas others are aggravating factors. They can impact whether or not a fit and proper certificate is issued in the first place and/or the actions that may need to be taken to mitigate or remediate a potential or identified risk to fitness and propriety. Of course, not all of the factors in the table will be relevant in every case.

Factors that may mitigate or aggravate the severity of an issue

| Specific circumstances | Intent | Was the incident deliberate or accidental (e.g. from not understanding firm processes)? |

| Frequency | How often has this happened? Was it a single incident? Is there a pattern? What does this suggest about causes or recurrence? | |

| Degree of harm or impact* | To what extent does the degree of actual or potential harm or impact (e.g. to customers, clients, members or colleagues) aggravate the seriousness of the issue? | |

| Level of experience | How experienced is the individual? What is the degree of influence they have within the firm? Should they have known better? | |

| Individual reaction | How did the individual react to the circumstances? Did they, for example, actively seek to correct a mistake or take ownership of the situation? | |

| Level of ongoing risk | How significant is the ongoing risk to the firm? | |

| Personal factors | Are there any personal mitigating or aggravating factors, such as illness or bereavement? | |

| Nature of evidence | How did the evidence come to light (e.g. self-declared as opposed to uncovered through screening or an investigation)? | |

| Relevance | If the evidence arose within the individual’s personal sphere (e.g. social media), to what degree is it relevant to their ability to perform in their role? | |

| Wider Context | Legal/regulatory context** | Are there relevant regulatory statements? Is the incident within the scope of the conduct rules? |

| Consistency with other firm decisions | What has the firm done in previous cases where there have been similar issues? What precedents might this decision set for the firm? | |

| Individual track record | What is the track record of this individual in the firm, or previously? Do they have a history of incidents that raise concerns, relating either to the same or different issues? | |

| Reputational impact | What is the potential reputational impact for the firm and/or the wider banking sector (e.g. a professional body)? Could it result in a loss of trust among customers, members and/or clients? | |

| Impact on other individuals | Does it raise questions over the F&P of any other employees (e.g. a line manager who has not provided sufficient oversight, or colleagues who may have been aware or involved)? | |

| Organisational considerations | Is there a wider issue within the firm? Are, for example, people in this role being incentivised to act in a certain way? Is there a controls or supervision failure in a specific area? |

* The degree of harm or impact caused may aggravate the severity of the issue, although lack of harm or impact (for example, an unsuccessful attempt to deceive) would be unlikely to provide mitigating circumstances.

** The impact of the regulatory environment and the Conduct Rules in particular will need to be considered early on in the assessment of risks and issues.

Assessing non-financial misconduct

When assessing an individual’s fitness and propriety, non-financial misconduct must be factored into the equation.

Non-financial misconduct is, essentially, conduct which take place outside of the workplace. Non-financial conduct is a central focus for the FCA at the moment. The line of cases under the SM&CR which provides guidance on this subject is, at the time of writing this training programme, still relatively small. Many of the cases which do exist focus on whether the individual in question lacks the “integrity” to be considered fit and proper to perform his or her (typically “his”) role.

Despite the fact that analysis of non-financial conduct may be in its relative infancy, one thing is for certain – non-financial misconduct must be taken into account by firms when assessing the fitness and propriety of their staff. Fortunately, there are already a number of lessons which firms can apply when considering whether the actions of staff members outside of the workplace has impacted on their fitness and propriety within the workplace. These can be summarised as being:

- The concept of “integrity” means adherence to ethical standards of the profession concerned.

- In matters regarding their professional standing there is an expectation that professionals may be held to a higher standard than those that would apply to individuals outside of the profession.

- Nevertheless, a regulatory obligation to act with integrity does not require professional people to be “paragons of virtue”.

- The need for public trust in the provision of professional services means that some scrutiny of a person’s private affairs is permitted.

- Requirements that professional persons act with integrity or be of sufficient repute may consider non-financial conduct only when the conduct that is part of a person’s private life realistically touches on their practice of the profession concerned. The conduct must be qualitatively relevant because it “engages” the standard of behaviour set out in the regulatory code concerned. It is not simply a question of assessing whether the behaviour concerned demonstrates a lack of integrity at large. Put simply, it must have some impact on the ability of the individual to do their job..

- In considering the question of whether conduct in a person’s private life touches on the practice of their profession, it is necessary to consider whether public confidence in the profession would be harmed if the public, assumed to have knowledge of the facts, found that a person who behaved in a manner under scrutiny was able to continue to practice his profession.

Determining an outcome

Issuing a certificate

Under section 63F of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, a fit and proper certificate must:

- state that the firm is satisfied that the person is fit and proper to perform the function to which the certificate relates; and

- set out the aspects of the affairs of the firm in which the person will be involved in performing the function.[1]

A fit and proper certificate is valid for a period of 12 months, beginning with the day on which it is issued. It can be drafted to expire sooner than 12 months, but cannot be drafted to remain valid for more than 12 months.[2]

In practice, for most staff members who have previously been certified as being fit and proper, provided that the evidence needed to assess basic fitness and propriety is kept up-to-date, the primary focus of fit and proper testing will be to determine how F&P can be maintained.

This is likely to involve identifying the actions necessary to pro-actively maintain fitness and propriety for a particular individual. In most cases, these actions will be preventative in nature. In and of itself, the act of identifying these actions should not usually mean that a fit and proper certificate cannot be issued for the individual under consideration.

However, in some circumstances it may be necessary to mitigate an actual or potential risk to fitness and propriety which has been identified (these are known as “Certification Risks”). In other circumstances, it may be necessary to take action to remedy an issue affecting fitness and propriety which has actually materialised (these are known as “Certification Issues”). We’ll give some consideration to both of these elements now.

[1] SYSC 27.2.9G

[2] SYSC 27.2.10G

Mitigating a Certification Risk

As previously mentioned, a “Certification Risk” is a situation that could potentially call into question an individual’s fitness and propriety, but has not yet materialised as an actual Certification Issue. In practice, a “Certification Risk” is likely to take one of two forms:

- Firstly, “Individual Certification Risks”, and

- Secondly, “Wider Certification Risks”.

As the name suggests, an “Individual Certification Risk” is specific to the person being assessed. Being a “Certification Risk” it has the potential to call into question that individual’s fitness and propriety.

An example of an “Individual Certification Risk” could be an individual who notifies the firm of the existence of a potential conflict of interest due to a family relationship with someone who holds a very senior position within a client firm. The individual does not currently have any professional contact with family member at the client firm, but could do so in future. The firm might mitigate this risk by preventing the individual from doing any kind of work for the client in question. It may be that this mitigating step requires the firm to create and implement additional internal controls.

A “Wider Certification Risk” tends to relate to the firm, rather than the individual. Often it will relate to structural or procedural issues. Nonetheless, it can still call into question the fitness and propriety of the individual being assessed. An example (given by the Banking Standards Board) would include inadequate controls in higher risk roles (for instance, inadequate controls in relation to individuals who are closely involved in transaction decisions, or who have access to privileged information or play an important part in settlement operations).

The Banking Standards Board guidance provides a non-exhaustive list of examples of “Individual Certification Risks” and “Wider Certification Risks” – as set out in this table.

| Category | Type of risk | Example scenario |

|---|---|---|

| Individual risk | Conflicts of interest | Are there any conflicts of interest that could call into question any element of the individual’s F&P, and have they declared them when required to do so? |

| Personal circumstances | Are there any personal circumstances specific to the individual, such as financial soundness, that could present a risk? | |

| Absence of information | Is there any information missing about the individual for any reason (such as criminal records checks being unavailable in an specific jurisdiction, or a full regulatory reference being unobtainable from all relevant previous employers)? | |

| Individual track record | What is the individual’s track record within the firm and is there anything that might flag risk, such as complaints that did not result in action against the individual? Were any risks raised in their regulatory reference? How much experience does the individual have within the firm and with the requirements of the role? | |

| Concentration of risks | Are there more risks associated with this person that would normally be expected for someone in this role? | |

| Wider Certification risk | Type and parameters of role | Are there aspects of the role that might affect where the firm sets its risk tolerances, e.g. close proximity to transaction decisions, privileged information or cash and settlement operations? |

| Whether the role was previously specifically regulated | Was this type of role previously regulated under the Approved Persons Regime, or are the requirements of the Certification Regime likely be new to the individual? | |

| Type of F&P assessment undertaken | What type of assessment is being undertaken? Is it e.g. a triggered assessment because of new information, or a new to role assessment for which the firm has little evidence of its own? |

Once a Certification Risk – whether Individual or Wider in nature – has been identified, a firm should proactively take steps to mitigate the Certification Risk with the objective not just of preventing it from turning into a Certification Issue, but of reducing its impact – hopefully to the point of remedy.

In most cases, neither the identification of a Certification Risk nor the implementation of measures to ameliorate a Certification Risk would prevent the firm from being able to issue a fit and proper certificate to the individual being assessed. Moreover, firms should recognise that, in practical reality, it is not possible to fully mitigate all Certification Risks. Nonetheless, there may be circumstances where a Certification Risk cannot be effectively mitigated to a point where it remains consistent with the firm’s own risk tolerances. If this is the case, the firm should not accept this risk and more drastic action may be required (for example, ceasing the underlying activity which is the root cause of the Certification Risk).

Remediating a Certification Issue

We have previously discussed how a Certification Issue is an issue affecting fitness and propriety which has ACTUALLY materialised.

Some Certification Issues will come to light as a result of the fit and proper assessment itself. However, many – perhaps the majority – will become apparent in other ways (for example, as a result of a complaint or a whistleblower).

The approach to Certification Issues differs from the approach to Certification Risks. When a Certification Issue is identified, the firm should take steps to satisfy itself that the Certification Issue can be remediated BEFORE it issues a fit and proper certificate with respect to the role in relation to which the Certification Issue was identified. What are the types of remediation measures that may have to be considered? Examples include the establishment of additional controls or processes, amendments to role descriptions and responsibilities, or the provision of additional training.

Depending on the seriousness of any Certification Issue which has been identified, a firm might choose to issue a fit and proper certificate with additional limitations or requirements. In practice, there is probably particular latitude to adopt this approach where the underlying Certification Issue relates to the individual’s competence. For example, it may be possible to issue a fit and proper certificate for an individual to perform a more restricted, or less senior, role whilst that individual acquires a particular qualification that would allow him or her to perform the role originally envisaged by the firm. In these circumstances, given that the individual will still fundamentally be performing his or her role, it would be sensible to consider issuing the fit and proper certificate for a period shorter than a year, and to diarise an IN-YEAR ASSESSMENT in order to gauge whether any remedial actions have been effective at that point (and whether it would be safe to remove any limitations or requirements at that stage).

Of course, if a Certification Issue was sufficiently serious to mean that it was not possible to issue a fit and proper certificate at the time of the initial assessment, it may still be possible to issue a fit and proper certificate with respect to the relevant individual at a later date. However, again, best practice would suggest that this should take place following an IN-YEAR ASSESSMENT. This would allow the firm to take stock of whether the remediation measures had achieved, or were on track to achieve, their desired objectives.

It goes without saying that where remediation actions are agreed, they need to be monitored – not just to confirm that they have actually been implemented, but also to confirm their effectiveness at remedying the Certification Issue. Again, this might necessitate an in-year assessment in order to ‘check-in’ on progress.

The Banking Standards Board also provides some examples of the types of remediation action that may be considered with respect to different types of Certification Issue. Their guidance is summarised in this table.

| Category | Example reason | Example action |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Certification Issue | The individual is not assessed as competent to perform their role. | Improvement plan to gain relevant qualifications, training or experience over a specified period. The firm adjusts the level and intensity of supervision and re-assesses the individual’s competence. |

| Poor performance not related to technical competence. | Addressed through the performance management process. | |

| The circumstances affecting fitness and propriety are expected to be temporary, e.g. the individual is new to the role or has had a change in circumstances. | Additional controls, appropriate level of supervision and/or support for a specified period. | |

| An individual declares a financial difficulty | Access to support, e.g. debt management plans, financial advice or financial aid; if necessary, additional oversight or controls. | |

| Agreed remediation plans require the firm to assess progress (such as improving performance issues). | In-year assessment (possibly in combination with other measures). | |

| Firm Certification Issue | Issue with the type of role rather than the individual filling it, such as a conflict of interest arising from the way in which the role is structured. | Additional controls, supervision and/or training for all relevant individuals and/or changes to the way that the role is structured. |

Individuals performing multiple Certification Functions

Questions arise as to the issuance of fit and proper certificates with respect to Certification Employees who perform multiple Certification Functions. On this topic, some things are clear:

- Firstly, a firm does NOT need to issue multiple fit and proper certificates for a single Certification Employee, even if that person performs more than one Certification Function (provided that it is part of the same job).

- Second, in a similar vein, a firm need NOT issue multiple fit and proper certificates for a single Certification Employee who performs a Certification Function that is made up of a number of different functions.

- An example of a Certification Function that is made up a number of different functions is the “material risk taker” Certification Function.

- SYSC 27.8.14R says that each function carried out by someone who is a “material risk taker” is itself a Certification Function.

- Nevertheless, a firm should assess whether a Certification Employee is fit and proper to perform ALL aspects of the employee’s functions that involve the performance of a Certification Function as described by a certificate.

- Moreover, although a firm does not need to issue multiple fit and proper certificates for a Certification Employee who performs several different Certification Functions, under the requirements in SUP 16.26 (Reporting of Directory persons) the firm will need to specify each of the Certification Functions which the employee has been assessed as fit and proper to perform and for which the employee has a certificate at the time of the report.[1]

- However, beyond this specific requirement, rather than issue multiple certificates, a firm may, in a single certificate, describe the employee’s functions that involve a Certification Function in broad terms, and without listing all the activities that the function may involve.

- A fit and proper certificate may cover functions that a Certification Employee is not currently performing, as long as the firm has assessed the employee’s fitness for these additional functions. However, when a firm is deciding what a fit and proper certificate can cover beyond the functions that the Certification Employee is currently performing, it should take the factors in SYSC 27.2.15G(2) into account. SYSC 27.2.15G(2) requires the firm to think about whether an individual has the necessary (a) personal characteristics, (b) level of competence, knowledge and experience, (c) qualifications, or (d) training, before determining that the individual is fit and proper to perform a function which he/she is not currently performing. More specifically, the FCA’s position is that a fit and proper certificate should not normally cover an additional function the firm has not considered the individual’s fitness and propriety with respect to each of these elements. Depending on the risk appetite of the firm, it is open to the firm to restrict a fit and proper certificate to the functions that the Certification Employee is currently performing rather than drafting the certificate more widely.

[1] SYSC 27.2.14G

The decision NOT to issue an F&P certificate

Section 63F(6) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 states that if, after having considered whether a person is fit and proper to perform a function, the firm decides NOT to issue a fit and proper certificate to the person, the firm must give the person a notice in writing stating—

- Firstly, what steps (if any) the firm proposes to take in relation to the person as a result of the decision, and

- Secondly, the reasons for proposing to take those steps.[1]

If a firm refuses to renew an individual’s certificate, the firm must take reasonable care to ensure the individual ceases to perform the Certification Function in question. In addition, if, after having considered whether a person is fit and proper to perform a Certification Function, a firm decides not to issue a certificate to that person, it should consider if the circumstances warrant making a notification to the FCA for a breach of the rules in COCON pursuant to SUP 15.3.11R.[2]

It is a simple fact of life that not all identified Certification Issues will be capable of remediation or cannot be satisfactorily remediated, given the firm’s internal risk tolerances. In addition, even the most well-conceived and best implemented remediation actions may fail to address a Certification Issue. That being the case, it is possible that a firm may reach the point where is decides that it is NOT possible to issue a fit and proper certificate.

Obviously, any decision NOT to issue a fit and proper certificate to an individual is a significant one. This is the case for the firm (who will need to consider WHY this decision was reached and what must be done as a consequence) but even MORE SO for the individual (who may now not be able to perform his or her role and has a potential ‘black mark’ against their name that may follow them around through their career due to the regulatory reference requirements of the SM&CR). This fact highlights how critically important it is for firms to provide clear guidance to those performing fit and proper assessments as to exactly when this ‘end of the line’ stage is reached and the factors that should be taken into account along the route of that journey. Staff performing fit and proper assessment should be given training on the need to fully consider all of the circumstances, all of the evidence, and all of the available options. Any member of staff who has been refused a fit and proper certificate should have a right of appeal against the decision. The appeal process should be overseen by someone who has sufficient authority and skill, and who was not involved in the original decision.

The Banking Standards Board provides some helpful examples of the factors which firms could consider when evaluating whether an issue can or cannot be remediated. Those factors are summarised in this table.

[1] SYSC 27.2.11G

[2] SYSC 27.2.12G

| Type of Remediation Issue | Factors why remediation may not be possible |

|---|---|

| Specific case not possible to remediate | Failure on the part of the individual to remediate an issue despite agreeing to do so (e.g. failing to attend required training or comply with new controls). |

| The cost / time / resource needed to remediate is disproportionate (e.g. it would take too long, cost too much or require resource that is not available). | |

| Type of issue not possible to remediate | The severity of the issue is too great (e.g. large-scale harm to customers and clients and/or reputation). |

| The type of issue involved means that remediation is inappropriate (e.g. deliberate dishonesty, serious misconduct, persistent or severe conduct rules breaches, criminal conduct). |

Particular consideration should be given to the case where an individual has ostensibly FAILED to implement agreed remediation actions, meaning that the Certification Issue itself remains. It may well be the case that there are legitimate reasons behind any such failure. However, even where this is the case, there may come the point where the firm must conclude that the individual – despite his or her best efforts – is simply incapable of remedying the Certification Issue to the extent required by the firm.

The failure by an individual to implement an agreed set of remediation actions may also result in disciplinary action being taken against that individual. It goes without saying that fit and proper assessments must take into account the results of any disciplinary process. It is possible that a disciplinary process results in the termination of the individual’s employment. In these circumstances, it is unlikely that any subsequent fit and proper assessment would be performed. Nevertheless, the outcome of the disciplinary proceedings must be recorded as they may be relevant if the need ever arises in the future to respond to a request for a regulatory reference about the individual in question. Depending on the circumstances, it may also be necessary to notify a regulator.

Conversely, an individual may choose to leave before the outcome of any fit and proper assessment (or any disciplinary proceedings) are concluded. In these circumstances, the firm will need to record the fact that the fit and proper assessment was not completed as this will be a relevant fact which may in future have to be provided to a party making a request for a regulatory reference about the individual in question.

Recording the outcome

The final stage of any fit and proper assessment is to record the outcome, not least because section 63F(7) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 requires every firm to maintain a record of every employee who has a valid fit and proper certificate issued by the firm.[1]

Of course, this should include information about Certification Risks and Certification Issues that have been identified, as well as the steps taken to mitigate them. With this information, it may be possible for firms to discern the root causes of issues and take more effective steps to mitigate or remedy.

[1] SYSC 27.2.13G

After the decision – ongoing fit and proper obligations

It goes without saying that, once an individual has been confirmed as being fit and proper to perform his or her role, the individual must also REMAIN fit and proper. In reality, this is an obligation which is shared by both the firm and the individual. For its part, the firm should provide all of the training and support the individual requires. It should also foster an open culture which minimises conflicts of interest and encourages staff members to be open regarding the issues faced by them personally and by the firm. For his or her part, the individual should actively participate in all necessary training to address any identified development needs and commit to pro-actively notifying their employer of any changes in personal circumstances that might adversely impact their fitness and propriety (such as a criminal record or a bankruptcy). Fundamentally, for individuals, it’s about accepting the personal responsibility which lies at the heart of SM&CR.